Note

This document was greatly inspired by:

Nelsen, Roger B. An introduction to copulas. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

Nelsen, Roger B. “Properties and applications of copulas: A brief survey.” Proceedings of the first brazilian conference on statistical modeling in insurance and finance. University Press USP Sao Paulo, 2003.

Chang, Bo. Copula: A Very Short Introduction.

Andy Jones. SCAD penalty.

A Deeper Intro to Copulas

For people who are more interested in knowing more about copulas, where they come from, computation challenges, and the mathematical intuition behind it, this is the document to read. We advise the reader to go through A Practical Introduction to Copula at first for basic concepts that will be assumed in this document.

Definition (Formal definition of bivariate copula) A two-dimensional copula is a function \(C: \mathbf{I}^2 \rightarrow \mathbf{I}\) where \(\mathbf{I} = [0, 1]\) such that

(C1) \(C(0, x) = C(x, 0) = 0\) and \(C(1, x) = C(x, 1) = x\) for all \(x \in \mathbf{I}\);

(C2) \(C\) is 2-increasing, i.e., for \(a, b, c, d \in \mathbf{I}\) with \(a \le b\) and \(c \le d\):

\[V_c \left( [a,b]\times[c,d] \right) := C(b, d) - C(a, d) - C(b, c) + C(a, c) \ge 0.\]

Keep in mind that the definition of copula \(C\) is just the joint cumulative density on quantiles of each marginal random variable (r.v.). i.e.,

And (C1)(C2) naturally comes from joint CDF: (C1) is quite obvious, and (C2) is just the definition of

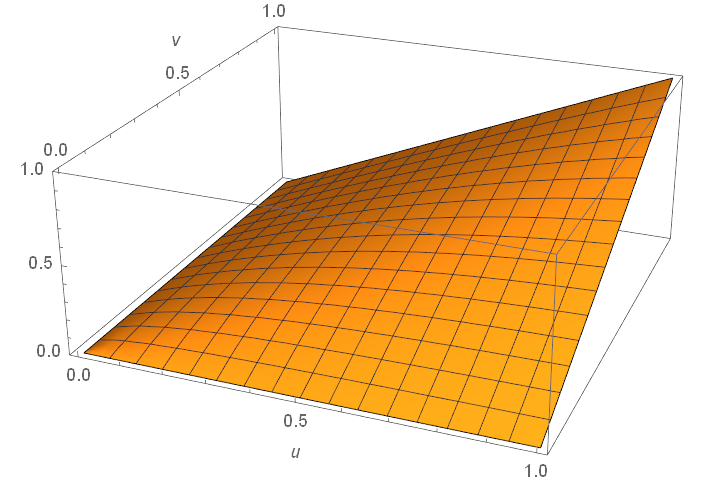

Plot of \(C(u,v)\) for an N13 copula.

A Few Useful Things

Before we begin, let us make it clear that this documentation is not meant to be purely theoretical, and we are treating copulas from an applied probability theory point of view with a focus on trading. To achieve this, we need to introduce a few useful concepts that will for sure help. To avoid getting lost in symbols, we only discuss bivariate copulas here.

Tail Dependence

Definition (Coefficients of lower and upper tail dependence) The lower and upper tail dependence are defined respectively as:

And those can be derived from the copula:

where \(\hat{C}(u_1, u_2) = u_1 + u_2 - 1 + C(1 - u_1, 1 - u_2)\) is the reflected copula. If \(\lambda_l > 0\) then there is lower tail dependence. If \(\lambda_u > 0\) then there is upper tail dependence. Note that one should actually calculate the limit for each copula, and it is not obvious from the plot usually.

For example, as plotted below, it can be calculated easily that for a Gumbel copula, \(\lambda_l=0\) and \(\lambda_u=1\).

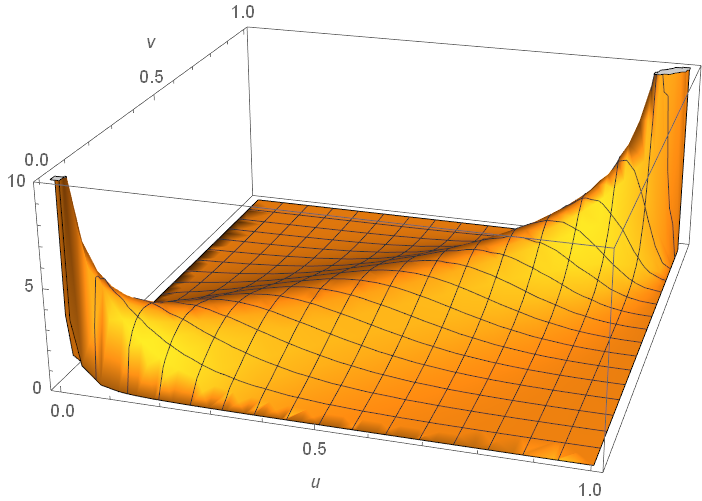

Plot of \(c(u,v)\) for a Gumbel copula. It has upper tail dependence but no lower tail dependence.

Fréchet–Hoeffding Bounds

Here is a handy theorem that holds true for all copulas, and is quite useful in analysis:

Theorem (Fréchet–Hoeffding Bounds for bivariate copulas) Consider a bivariate copula \(C(u_1, u_2)\), then for \(u_j \in \mathbf{I}\):

The lower bound comes from the counter-monotonicity copulas whereas the upper bound comes from the co-monotonicity copulas. co-monotone means the two marginal random variables are perfectly positively dependent, for instance, \(X_2 = 3 X_1\). In this case their quantiles are identical and we have:

Similarly, counter-monotone means the two random variables are perfectly negatively dependent, for instance, \(X_2 = -5 X_1\).

Empirical Copula

At first, a copula always exists for two continuous random variables (to avoid ties in percentile) \(X_1\), \(X_2\), guaranteed by Sklar’s theorem. Once we have enough observations from \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), we define the implied bivariate empirical copula as follows:

where \(X_1(i)\) is the \(i\)-th largest element for \(X_1\); same applies for \(X_2(j)\); \(|| \cdot ||\) is the cardinality, or the number of elements in the set for a finite set. The definition may look more complicated than what it is. To calculate \(\tilde{C}_n(\frac{i}{n}, \frac{j}{n})\), one just need to count the number of cases in the whole observation that are not greater than the \(i\)-th and \(j\)-th rank for their own marginal r.v. respectively.

The empirical copula can also be defined parametrically by finding each margincal CDF \(F_1\), \(F_2\). In that case, the empirical copula becomes:

If one uses empirical CDFs, then it is identical to our first definition.

Note

Implicitly, copula is used to model independent draws from multiple time-invariant r.v.’s and analyze their dependency structure without influence from the specific marginal distributions. When applying copula to time series, obviously each draw is not independent, and the dependency between securities is likely to change as time progresses. Therefore, using an empirical copula may not be a good idea.

Also, using a non-parametric empirical copula for trading may “downscale” the strategy into its simpler counterparts that one may aim to improve upon in the beginning. For example, since most copula-based trading strategies uses conditional probabilities to signal thresholds. If one directly uses an empirical copula, then it technically becomes a rank-based distance method: Simply look at the history and see how unlikely such mispricing events happens. If they are really mispriced based on ranks then open a position. This rather common strategy may already be overused and not generate enough alpha. Plus, one will lose the ability to carefully model the tail dependencies at their own desire.

“Pure” Copulas

Note

“Pure” copula is not an official name. It is used here for convenience, in contrast to mixed copulas, to represent Archimedean and elliptical copulas.

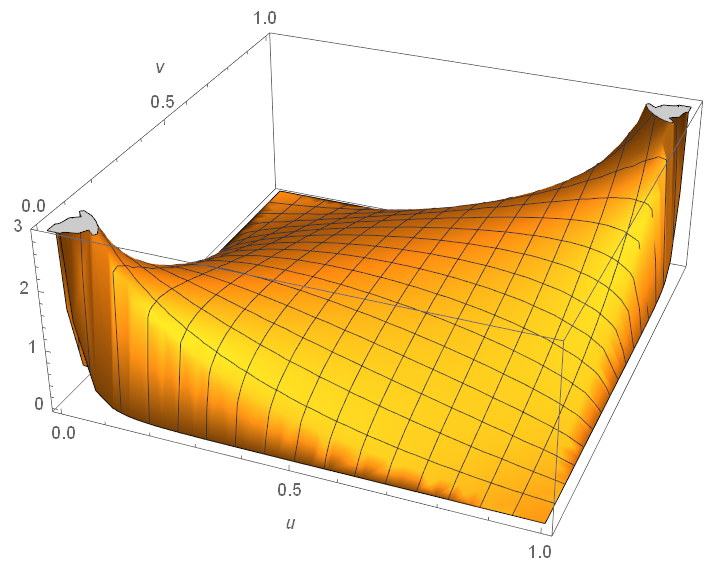

Plot of \(c(u,v)\) for the infamous Gaussian copula. It is often not obvious to decide from the plot that whether a copula has tail dependencies.

For practical purposes, at least for the implemented trading strategies in this module, it is enough to understand tail dependency for each copula and what structure are they generally modeling, because sometimes the nuances only come into play for a (math) analyst. Here are a few key results:

Upper tail dependency means the two random variables are likely to have large values together. For instance, when working with returns series, upper tail dependency implies that the two stocks are likely to have large gains together.

Lower tail dependency means the two random variables are likely to have small values together. This is much stronger in general compared to upper tail dependency, because stocks are more likely to go down together than going up together.

Frank and Gaussian copulas do not have tail dependencies at all. And Gaussian copula infamously contributed to the 2008 financial crisis by pricing CDOs exactly for this reason. Frank copula has a stronger dependence in the center compared to Gaussian.

For fitting prices and returns data, usually Student-t comes top score. Also it does not give probabilities far away from an empirical copula.

For Value-at-Risk calculations, Gaussian copula is overly optimistic and Gumbel is too pessimistic.

Copulas with upper tail dependency: Gumbel, Joe, N13, N14, Student-t.

Copulas with lower tail dependency: Clayton, N14 (weaker), Student-t.

Copulas with no tail dependency: Gaussian, Frank.

Since a Student-t copula will converge to a Gaussian copula as the degrees of freedom increases, it makes sense to quantify the change of tail dependence (the upper and lower tail dependency is the same value thanks to symmetry for Student-t copula). It is tabled below from [Demarta, McNeil, The t Copula and Related Copulas, 2005]:

\(\nu \downarrow, \rho \rightarrow\) |

-0.5 |

0 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2 |

0.06 |

0.18 |

0.39 |

0.72 |

1 |

4 |

0.01 |

0.08 |

0.25 |

0.63 |

1 |

10 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.08 |

0.46 |

1 |

\(\infty\) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Creating own copulas

A user can create one of Archimedean or elliptical copula object and play around with it.

Archimedean copulas

Note

All copula classes in this module share the same basic public methods.

Here we only demonstrate all methods for the Gumbel copula class, as an example. All other classes have the same methods available

Elliptical copulas

Note

Elliptical copulas (Gaussian and T-Student copulas) can also work in N-dimensional space, however current implementations only support a 2-dimensional case. Multi-dimensional elliptical copulas will be added in future updates of ArbitrageLab.

Note

For Student copula, there is a special function used to find optimal \(\nu\) parameter for Student distribution used in Student Copula.

Examples

# Importing the functionality

from arbitragelab.copula_approach.archimedean import Gumbel

from arbitragelab.copula_approach.elliptical import StudentCopula, fit_nu_for_t_copula

cop = Gumbel(theta=2)

# Check copula description

descr = cop.describe()

# Get cdf, pdf, conditional cdf

cdf = cop.get_cop_density(0.5, 0.7)

pdf = cop.get_cop_eval(0.5, 0.7)

cond_cdf = cop.get_condi_prob(0.5, 0.7)

# Sample from copula

sample = cop.sample(num=100)

# Fit copula to some data

cop.fit([0.5, 0.2, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0.99],

[0.1, 0.02, 0.9, 0.22, 0.11, 0.79])

print(cop.theta)

# Generate copula plots

cop.plot_scatter(200)

cop.plot_pdf('3d')

cop.plot_pdf('contour')

cop.plot_cdf('3d')

cop.plot_cdf('contour')

# Creating Student copula

nu = fit_nu_for_t_copula([0.5, 0.2, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0.99],

[0.1, 0.02, 0.9, 0.22, 0.11, 0.79])

student_cop = StudentCopula(nu=nu, cov=None)

student_cop.fit([0.5, 0.2, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0.99],

[0.1, 0.02, 0.9, 0.22, 0.11, 0.79])

Applying copula to empirical data

As it was previously discussed, in order to use copula, one first needs to fit it on empirical data and find its corresponding parameter - theta for Archimedean copulas and rho/cov for elliptical.

However, copulas take only pseudo-observations distributed in

\([0, 1]\). One can either use statsmodels.distributions.empirical_distribution.ECDF or ArbitrageLab’s function

construct_ecdf_lin which is a slight modification of statsmodels’ ECDF with linear interpolation between data points.

However, one can fit several copulas to the same dataset. The question is: “Which copula suits best for the empirical data?”

Usually, one can either use:

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Schwarz information criterion (SIC).

Hannan-Quinn information criterion(HQIC).

All of the information criteria use log_likelihood from get_log_likelihood_sum function for estimation.

The best copula is the one that yields the minimum AIC, SIC or HQIC value.

On the other hand, one can just use the ArbitrageLab function which takes empirical data -> gets ECDFs -> fits copula, and returns fit copula object. It also returns fit ECDF(x), ECDF(y) functions, and information criterion values which can be used to find the best copula for the current dataset.

Examples

# Importing the functionality

import pandas as pd

from arbitragelab.copula_approach import fit_copula_to_empirical_data

from arbitragelab.copula_approach.archimedean import (Gumbel, Clayton, Frank,

Joe, N13, N14)

from arbitragelab.copula_approach.elliptical import (StudentCopula,

GaussianCopula)

# Importing data

bkd_prices = pd.read_csv('BKD.csv', index_col=0)

esc_prices = pd.read_csv('ECS.csv', index_col=0)

bkd_returns = bkd_prices.pct_change().dropna()

esc_returns = esc_prices.pct_change().dropna()

# All Archimedean and Elliptical copulas to fit

copulas = [Gumbel, Clayton, Frank, Joe, N13, N14, GaussianCopula, StudentCopula]

aics = dict()

for cop in copulas:

info_crit_logs, fit_copula, ecdf_x, ecdf_y = fit_copula_to_empirical_data(x=bkd_prices,

y=esc_returns,

copula=cop)

aics[info_crit_logs['Copula Name']] = info_crit_logs['AIC']

# AIC values for all copulas

print(aics)

Mixed Copulas

In this copula_approach module, we support two mixed copula classes: CFGMixCop for Clayton-Frank-Gumbel mix and

CTGMixCop for Clayton-Student-Gumbel mix, inspired by [da Silva et al. 2017].

It is pretty intuitive to understand, for example, for a CFG mixed copula, one needs to specify the \(\theta\)’s, the dependency parameter for each copula component, and their weights that sum to \(1\). In total there are \(5\) parameters for CFG. The weights should be understood in the sense of Markov, i.e., it describes the probability of an observation coming from each component.

For example, we present the Clayton-Frank-Gumbel mixed copula as below:

Why Mixed Copulas

Archimedean copulas and elliptical copulas, though powerful by themselves to capture nonlinear relations for two random variables, may suffer from the degree to which they can be calibrated to data. While using a pure empirical copula may subject to overfiting, a mixed copula that can calibrate the upper and lower tail dependency usually describes the dependency structure really well for its flexibility.

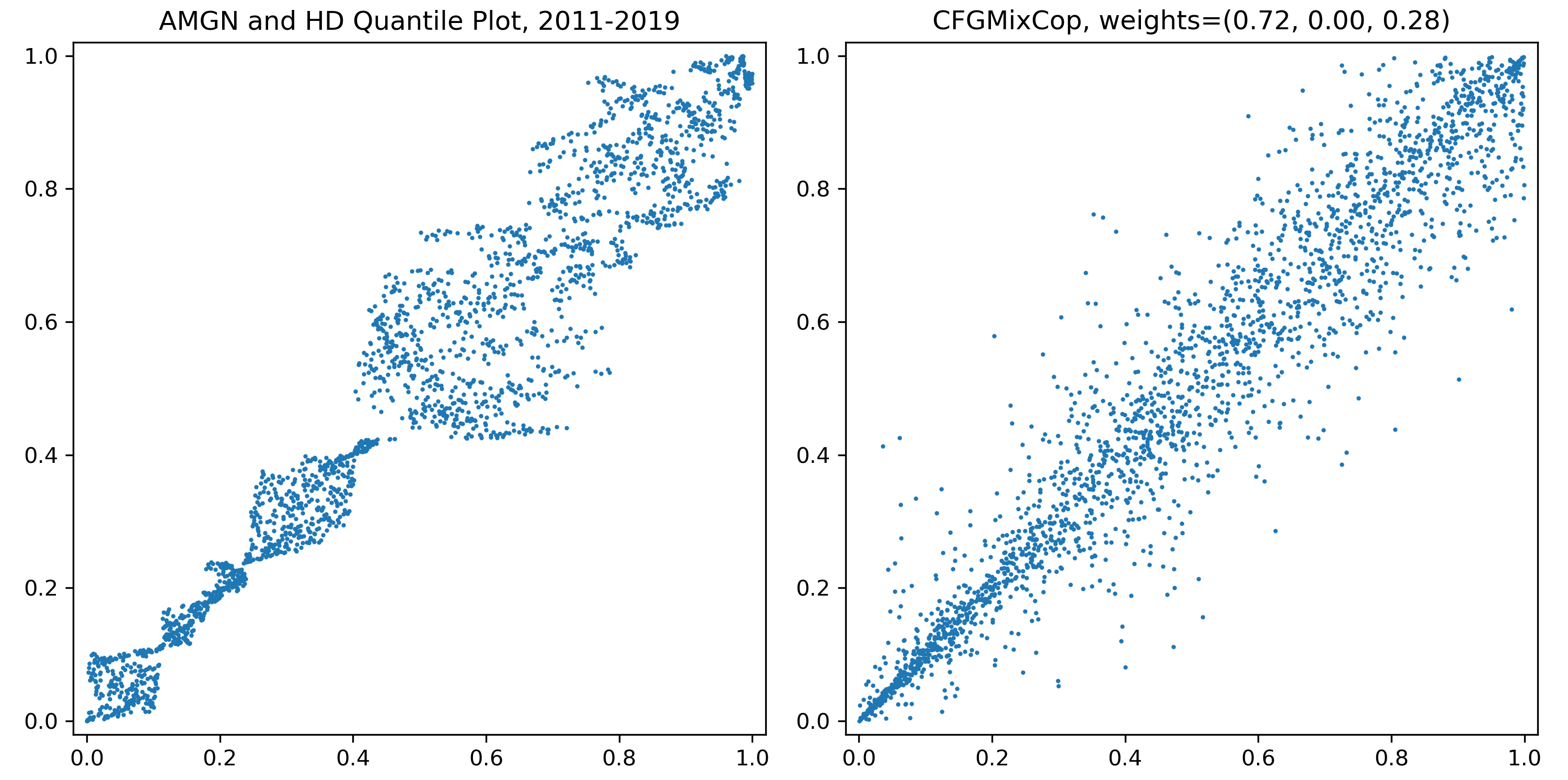

Plot of quantiles for prices of Amgen and Home Depot in 2011-2019, and sample plots from a fitted CFG copula. Mixed copulas calibrate the tail dependencies better than “pure” copulas.

But this flexibility comes at a price: fitting it to data is not trivial. Although one can wrap an optimization function for finding the individual weights and copula parameters using max likelihood, realistically this is a bad practice for the following reasons:

The outcome is highly unstable, and is heavily subject to the choice of the maximization algorithm.

A maximization algorithm fitting \(5\) parameters for CFG or \(6\) parameters for CTG usually tends to settle to a bad result that does not yield a comparable advantage to even its component copula. For example, sometimes the fit score for CTG is worse than a direct pseudo-max likelihood fit for Student-t copula.

Sometimes there is no result for the fit, since the algorithm does not converge.

Some maximization algorithms use Jacobian or Hessian matrix, and for some copulas the derivative computation is not numerically stable.

Often the weight of a copula component is way too small to be reasonable. For example, when an algorithm says there is \(0.1 \%\) Gumbel copula weight in a dataset of \(1000\) observations, then there is on average \(1\) observation that comes from Gumbel copula. It is bad modeling in every sense.

EM Fitting Algorithm

Instead, we adopt a two-step expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm for fitting mixed copulas, adapted from [Cai, Wang 2014]. This algorithm addresses all the above disadvantages of a generic maximization optimizer. The only downside is that, the CTG copula may take a while to converge to a solution for certain data sets.

Suppose we are working on a three-component mixed copula of bivariate Archimedeans and ellipticals. We aim to maximize over the objective function for copula parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and weights \(\mathbf{w}\).

where \(T\) is the length of the training set, or the size of the observations; \(k\) is the dummy variable for each copula component; \(p_{\gamma, a}(\cdot)\) is the smoothly clipped absolute deviation (SCAD) penalty term with tuning parameters \(\gamma`and :math:`a\) and it is the term that drives small copula components to \(0\); and last but not least \(\delta\) the Lagrange multiplier term that will be used for the E-step is:

E-step

Iteratively calculate the following using the old \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\) until it converges:

M-step

Use the updated weights to find new \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), such that \(Q\) is maximized. One can use truncated Newton or Newton-Raphson for this step. This step, though still a wrapper around some optimization function, is much better than estimating the weights and copula parameters all together.

We then iterate the two steps until it converges. It is tested that the EM algorithm is oracle and sparse. Loosely speaking, the former means it has good asymptotic properties, and the latter says it will trim small weights off.

Note

The EM algorithm is still not mathematically perfect, and has the following issues:

It is slow for some data sets. Also the CTG is slow due to the bottleneck from Student-t copula.

If the copulas mixture have similar components, for instance, Gaussian and Frank, then it cannot pick the correct component weights well. Luckily for fitting data, usually the differences are minimal.

The SCAD parameters \(\gamma\) and \(a\) may require some tuning, depending on the data set it fits. Some authors suggest using cross validation to find a good pair of values. We did not implement this in the package because it takes really long for the calculation to a point it becomes unrealistic to run it (about 1 hour in some cases). We did run some CV while coding it, so that the default values of \(\gamma\) and \(a\) are good choices.

Sometimes the algorithm throws warnings, because the optimization algorithm underneath does not strictly follow the prescribed bounds. Usually this is not an issue that will compromise the result. And some minor tuning on SCAD parameters can solve this issue.

Implementation

Note

All mixed copula classes share the basic public methods in this module. Hence here we only demonstrate one of them for example. Mixed copulas have their own dedicated fitting method, compared to “pure” copulas.

Interesting Open Problems

Parametrically fit a Student-t and mixed copula.

Existence of statistical properties that justify two random variables to have an Archimedean copula (like one can justify a random variable is normal).

Take advantage of copula’s ability to capture nonlinear dependencies but also adjust it for time series, so that the sequence of data coming in makes a difference.

Analysis on copulas when it is used on time series instead of independent draws. (For example, how different it is when working with the average \(\mu\) on time series, compared to the average \(\mu\) on a random variable?)

Adjust copulas so it can model when dependency structure changes with time.

All copulas we mentioned so far, “pure” or mixed, assume symmetry. It would be nice to see analysis on asymmetric pairs modeled by copula.